Recursive Descent Parser

2016-04-18

Generally I advise people who write parsers to use parser generation tools such as bison and flex. But with small languages it may be advisable to write your own recursive descent parser.

To illustrate how to write a recursive descent parser, I will show you around a parser I wrote a while ago for INI style configuration files. The parser in question is the parse for the cfg library:

Anatomy of a Parser

But before we go into the code, first a little bit of theory.

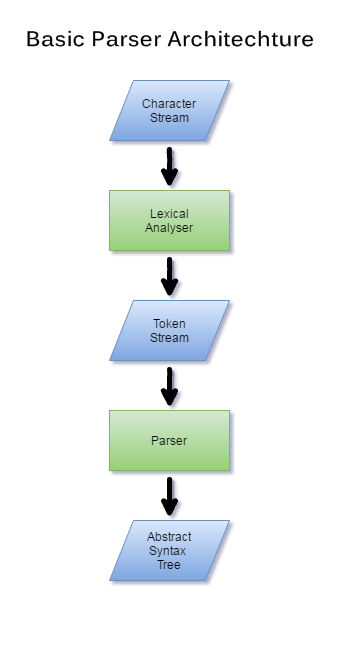

Parser are generally split into two bits, the lexical analyser (lexer) and the actual parser. The lexical analyser takes a stream of characters from a file or any other source and converts this to a stream of tokens. These tokens are then consumed by the parser and converted into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

If you would write a compiler for a programming language, you would now pass the AST to an optimizer and code generator. But when reading simple data you omit these steps and just generate the data.

The cfg Format

The cfg format is similar to the INI format, but not with such a lax syntax.

As an example:

# Default Configuration

[Graphic]

width = 800

height = 600

fullscreen = false

[Input]

forward = W

backward = S

left = A

right = D

jump = SPACE

[Server]

message = "Welcome to my server!\nIt rocks!"

As you can see comments are prefixed with an octothorpe and span an entire line. The file is split into sections and each section is enclosed by square brackets. The values in sections are denoted with a key, that is an identifier and a value that may be an identifier, a number or a string.

No article about building parsers would be complete without an EBNF. So here is the cfg format in EBMF notation:

cfg = sections;

sections = section sections;

section = section_header values | empty_line;

section_header = "[" identifier "]" nl;

values = key_value_pair values;

key_value_pair = identifier "=" value nl | empty_line;

value = identifier | number | string

empty_line = nl;

identifier = /[a-ZA-Z_][a-zA-Z0-9_\-]/;

number = /(-|+)?[0-9]+(\.[0-9]+)?/;

string = /\"[^\r\n]*\"/;

nl = "\n" | "\r" | "\r\n";

discard = ws | comment;

ws = /[ \t\v]/;

comment = /#[^\r\n]*/;

Note: The string rule not is correct, the actual implementation is "like C", but making that a proper regex & EBNF is really messy, so this simple stand-in will do.

Note: This format allows identifiers with minus signs. (e.g. valid-identifier)

The Lexer

When writing small parsers like this, I tend not write a specific lexer class, so all the lexer elements are integrated into the cfg::Parser class. This makes a few things, like error reporting simpler.

Tokens are identified by the Token enum:

enum Token

{

NO_TOKEN,

WHITESPACE,

OPEN_BRACE,

CLOSE_BRACE,

EQUALS,

IDENTIFIER,

STRING,

NUMBER,

NEWLINE,

COMMENT,

FILE_END,

ERROR

};

You see all tokens from the EBNF and a few extra tokens, like NO_TOKEN, COMMENT, FILE_END and ERROR. Their use is obvious. A special note is the ERROR token, this token would be emitted when a lexing error occurred and then the parser could perform error recovery. This is why you see more than one error in your C++ compiler. But in this case the error function will simply throw an exception and the ERROR token is never emitted in this parser. I still use it to satisfy the compiler.

The interface between the parser and the lexer is the get_next_token function:

Token get_next_token(std::string& value);

The function returns the current token type and the string that was read.

The lexer has one important feature, it is implemented with one token look

ahead. This is important, since it allows the parser to make an informed

decision which branch to follow down the parsing tree. So you may occasionally

the the parser peeking at the next_token variable.

Tip: Always return the value as a string. You may be tempted to union style value like bison uses that contains integer and float values. The problem is once you convert the string to an integer, you are committed to the type and loss of precision is a guarantee. You should handle it as a string until you know for sure in the parser what type it will be.

Parser::Token Parser::get_next_token(std::string& value)

{

Token token = next_token;

value = next_value;

next_token = lex_token(next_value);

while (next_token == WHITESPACE || next_token == COMMENT)

{

next_token = lex_token(next_value);

}

return token;

}

The get_next_token function implements the one token look ahead and the discard

rule. The actual lexing is done in lex_token and it's sister functions.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_token(std::string& value)

{

value.clear();

int c = in->get();

switch (c)

{

case ' ': case '\t': case '\v':

value.push_back(c);

return lex_whitespace(value);

case '\n': case '\r':

value.push_back(c);

return lex_newline(value);

case '0': case '1': case '2': case '3': case '4':

case '5': case '6': case '7': case '8': case '9':

case '-': case '+':

value.push_back(c);

return lex_number(value);

case 'a': case 'b': case 'c': case 'd': case 'e': case 'f':

case 'g': case 'h': case 'i': case 'j': case 'k': case 'l':

case 'm': case 'n': case 'o': case 'p': case 'q': case 'r':

case 's': case 't': case 'u': case 'v': case 'w': case 'x':

case 'y': case 'z':

case 'A': case 'B': case 'C': case 'D': case 'E': case 'F':

case 'G': case 'H': case 'I': case 'J': case 'K': case 'L':

case 'M': case 'N': case 'O': case 'P': case 'Q': case 'R':

case 'S': case 'T': case 'U': case 'V': case 'W': case 'X':

case 'Y': case 'Z':

case '_':

value.push_back(c);

return lex_identifier(value);

case '"':

return lex_string(value);

case '[':

value = "[";

return OPEN_BRACE;

case ']':

value = "]";

return CLOSE_BRACE;

case '=':

value = "=";

return EQUALS;

case '#':

return lex_comment(value);

case EOF:

return FILE_END;

default:

value.push_back(c);

error("Unexpected " + value + ".");

return ERROR;

}

}

The lex_token function decides what actual token to lex based on the first character

encountered. (If you ever wondered why in most programming languages you can't

use identifiers that begin with a number, this is why.) Simple one character

tokens are immediately converted into a token and value.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_whitespace(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

while (true)

{

switch (c)

{

case ' ': case '\t': case '\v':

value.push_back(c);

break;

default:

in->unget();

return WHITESPACE;

}

c = in->get();

}

}

The lex_whitespace shows the essence all the lex function. While the function

encounters white spaces, it continues to read the character stream. If it

encounters something else it "ungets" the last character and returns.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_newline(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

line++;

switch (c)

{

case '\n': case '\r':

if (c != value[0])

{

// \r\n or \n\r

value.push_back(c);

}

else

{

// treat \n \n as two newline, obviously

in->unget();

}

return NEWLINE;

default:

in->unget();

return NEWLINE;

}

}

The lex_newline is mildly different, in that the "\r\n" rule is implemented.

Here the not quite correct "\n\r" is also accepted, but that is rather for

convenience. Also the lex_newline function increments the line counter, but

more about that later.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_number(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

while (true)

{

// NOTE: not validating the actual format

switch (c)

{

case '0': case '1': case '2': case '3': case '4':

case '5': case '6': case '7': case '8': case '9':

case '.':

value.push_back(c);

break;

default:

in->unget();

return NUMBER;

}

c = in->get();

}

}

This lex_number function is the bare bones to lex a number. If you need

specific format compliance you may want to extend the function. This function

accepts anything that is a number or a dot. So in theory, this function will

also accept IP-addresses.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_identifier(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

while (true)

{

switch (c)

{

case '0': case '1': case '2': case '3': case '4':

case '5': case '6': case '7': case '8': case '9':

case 'a': case 'b': case 'c': case 'd': case 'e': case 'f':

case 'g': case 'h': case 'i': case 'j': case 'k': case 'l':

case 'm': case 'n': case 'o': case 'p': case 'q': case 'r':

case 's': case 't': case 'u': case 'v': case 'w': case 'x':

case 'y': case 'z':

case 'A': case 'B': case 'C': case 'D': case 'E': case 'F':

case 'G': case 'H': case 'I': case 'J': case 'K': case 'L':

case 'M': case 'N': case 'O': case 'P': case 'Q': case 'R':

case 'S': case 'T': case 'U': case 'V': case 'W': case 'X':

case 'Y': case 'Z':

case '_': case '-':

value.push_back(c);

break;

default:

in->unget();

return IDENTIFIER;

}

c = in->get();

}

}

The lex_identifier function is the again similar. The thing to note here is

that in contrast to lex_token the numbers and minus sign are included here.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_string(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

while (true)

{

switch (c)

{

case '"':

return STRING;

case '\n': case '\r': case EOF:

error("Unexpected newline in string.");

return ERROR;

case '\\':

c = in->get();

switch (c)

{

case '\'':

value.push_back('\'');

break;

case '"':

value.push_back('"');

break;

case '\\':

value.push_back('\\');

break;

case 'a':

value.push_back('\a');

break;

case 'b':

value.push_back('\b');

break;

case 'f':

value.push_back('\f');

break;

case 'n':

value.push_back('\n');

break;

case 'r':

value.push_back('\r');

break;

case 't':

value.push_back('\t');

break;

case 'v':

value.push_back('\v');

break;

default:

error("Unknown escape sequence.");

break;

}

break;

default:

value.push_back(c);

break;

}

c = in->get();

}

}

The lex_string function is slightly more interesting. Firstly this function

works on the inverse, if it sees a quotation mark or newline it exists. This

function also implements the special case when encountering a backslash. If that

happens, it reads an additional character and then converts the result into

the proper escaped value. This also solves escaped quotation marks.

Parser::Token Parser::lex_comment(std::string& value)

{

int c = in->get();

while (true)

{

switch (c)

{

case '\n': case '\r': case EOF:

return COMMENT;

default:

value.push_back(c);

break;

}

c = in->get();

}

}

The lex_comment function is again similar to the string function, it reads

indiscriminately until it sees the end of the line.

The Parser

The public API of the parser consists of the constructor and the parse

function:

Parser(Config& config);

void parse(std::istream& in, const std::string& file = "", unsigned int line = 1);

The constructor just takes the resulting data object and initializes everything:

Parser::Parser(Config& c)

: config(c), in(nullptr), next_token(NO_TOKEN) {}

The parse function is the external driver and implements the cfg and sections rules:

void Parser::parse(std::istream& i, const std::string& f, unsigned int l)

{

in = &i;

file = f;

line = l;

// prep the look ahead

std::string dummy;

get_next_token(dummy);

while (next_token != FILE_END)

{

if (next_token == NEWLINE)

{

// skip empty lines

get_next_token(dummy);

}

else

{

parse_section();

}

}

}

The parse function starts with setting everything up. This includes running the

lexer once. This is needed because the the look ahead needs read the first token.

This could be done in the get_next_token function, but this saves us one if.

The remainder implements the sections rule. That is it reads sections while not having reached the end of file. Because the format is line sensitive, it also need to handle the case of empty lines (e.g. containing comments) before and sections. (Empty lines between sections are consumed in the key_value_pair rule.)

void Parser::parse_section()

{

parse_section_header();

while (next_token == IDENTIFIER || next_token == NEWLINE)

{

parse_value_pair();

}

}

The parse_section function simple delegates it's processing to the

parse_section_header and parse_value_pair functions. Here you can

see the look ahead in action to make a parsing decision. As long

as the parser sees either a new line (empty line) or an identifier (key value pair)

it continues executing the values loop. As you can seem the the values rule is

implicitly coded here. If you really like, you can follow the grammar more

closely and wrap it into a function; but I tend to take a pragmatic approach.

(Also, I defined the exact grammar a posteriori.)

void Parser::parse_section_header()

{

std::string value;

Token t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != OPEN_BRACE)

{

error("Expected open breace.");

}

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != IDENTIFIER)

{

error("Expected identifier.");

}

section = value;

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != CLOSE_BRACE)

{

error("Expected close brace.");

}

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != NEWLINE && t != FILE_END)

{

error("Expected newline.");

}

}

The parse_section_header function implements the simple checks to validate

the section_header rule. Here the semantic value of the identifier is stored

in the section member variable. This value will be later used to define actual

values.

void Parser::parse_value_pair()

{

std::string value;

Token t = get_next_token(value);

if (t == NEWLINE)

{

// accept empty line

return;

}

if (t != IDENTIFIER)

{

error("Expected identifier.");

}

std::string name = value;

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != EQUALS)

{

error("Expected equals.");

}

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != IDENTIFIER && t != STRING && t != NUMBER)

{

error("Expected identifier or string.");

}

config.set_value(section, name, value);

t = get_next_token(value);

if (t != NEWLINE && t != FILE_END)

{

error("Expected newline.");

}

}

The parse_value_pair function implements the validation and reading of the

key_value_pair rule. The somatic values of the key and value are then stored

in the configuration object, the final data form. At this place it may be

sensible to convert the semantic values into the corresponding data types.

But since the Config object stores it's values as strings, this step is

skipped.

Error Reporting

Finally onto the error reporting. The error function used all over the place in the parser. Here is the actual implementation:

void Parser::error(const std::string& msg)

{

std::stringstream buff;

if (!file.empty())

{

buff << file;

}

buff << "(" << line << "): " << msg;

throw std::runtime_error(buff.str());

}

The error function takes the line and file info with the error message and

makes a nice "file(line): msg" string and throws it via a runtime_error.

If you are writing a parser for a programing language you may want to look into error recovery. The basic idea it to log the error onto some error stream and return the ERROR token. Then one of the overlaying functions then try to find the next token that makes sense and continue parsing from there. But since this format is so simple and should be correct a single error is sufficient.

Conclusion

Writing recursive descent parser is quite simple for simple formats and is way less daunting than trying to work with bison and flex (or any other parser generator).